‘SEADRIFT’ DOCUMENTARY

USES 4K IMAGERY TO CHART UNFORESEEN WATERS

By Randall P. Dark

Partner, DARKmania Productions

When I decided to shoot Seadrift vs. The Big Guy, my original

premise was to follow the story of Jeff McAdams, a funny,

larger-than-life character who decided to tackle the Texas Water

Safari. Arguably the toughest canoe race in the world, it’s a nonstop,

260-mile race with a 100-hour deadline. A brash, overweight Texan who

smoked and drank – and hadn’t been in a canoe since he was a boy scout

– Jeff was the perfect subject for a lighthearted feature documentary

about man versus nature.

The race began at 9 a.m. on June 9, 2012, in San Marcos, Tex., which is

about 30 minutes south of Austin. We had decided to follow some other

racers during the event to create additional story arcs and juxtapose

the serious athletes from our unlikely hopeful. As expected, the race

was filled with adventure, but we never bargained for some of the chaos

and tragedy that unfolded.

Seadrift vs. The Big Guy is a fun adventure that also serves as a

cautionary tale for people who participate in extreme sports. It’s also

a teaching tool for aspiring documentary filmmakers, as it shows how

the story you think you’re going to tell always changes.

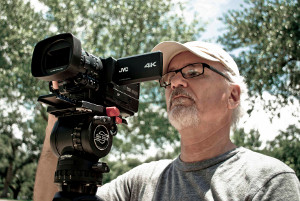

Logistically, covering a canoe race of this magnitude was a difficult

task, and we used a number of different cameras to enhance the

storytelling. By the end of the shoot, we had used a total of 21

cameras in 14 varieties. Our equipment list included the JVC GY-HMQ10

4K compact handheld camcorder, plus traditional HD camcorders, DSLRs,

and sunglass camera systems. We even relied on iPhones when one

competitor pulled a surprise marriage proposal and an iPad when Jeff

was laid up in bed after his back surgery.

Of course with so many cameras, image quality was inconsistent, but the

documentary was more about the story than the quality of the image

sensor. I’m a storyteller, not a technology snob. I’m a firm believer

that you work with the best tools you have to tell the best story you

can. If your audience is emotionally connected to the material, they

won’t be worried about resolution.

That said, I relied on JVC’s GY-HMQ10 to capture some amazing 4K

footage, such as a wide shot of the 140 boats starting the race. But I

also knew I could get away with lower-resolution images for other

shots, such as underwater footage and POV content from GoPro wearable

cameras. These days, even 1080i footage from a small sensor looks good.

This was my first project with the GY-HMQ10. I had high expectations –

and it met them. It was perfect for this documentary, because I needed

something portable and reliable that would capture a lot of picture

information.

Once the race started, the production team was in a constant state of

chasing the competitors. A full-sized camera would be more difficult to

manage on the riverbank; much of our footage was run-and-gun, because

we often didn’t have time to break out the tripod to get the shot. I

was able to capture really beautiful images with a very, very portable

camera. The JVC 4K camera performed flawlessly in the Texas heat, and I

had no issues with battery life.

I thought the 4K footage might cause some problems in post for my

editor, Adrianne Parent, but it was actually a pretty straightforward

process. First, we connected the GY-HMQ10 to my computer via USB and

opened JVC’s Clip Manager software. Once accessed, the software showed

thumbnails of the recorded clips. We selected the clips we wanted to

transcode, hit the export button, and chose which ProRes codec to use

for the conversion. (We used regular ProRes422.)

The converted footage was full resolution 3840x2160 ProRes422 files

that could be used immediately. However, because my deliverables were

not 4K and my system was not designed to handle files of that size, I

downconverted the footage to a more manageable 1920x1080 frame size

using Apple Compressor. The transcoding took some time, but then the

files could be used in my Final Cut Pro ProRes422 timeline and

integrated with footage from other sources without rendering.

With so many sources, color matching was definitely a challenge in

post. The color from the GY-HMQ10, for example, was phenomenal, so we

had to punch up the color from other cameras. Had this been a

documentary on butterflies, for example, all the different color

processing from all the different cameras would have been wacky. Even

with color correction, the finished product would just not look

consistent.

But this was a documentary about a canoe race shot across hundreds of

miles of river at various times of the day and night. As long as the

green tint of the water was close and flesh tones looked like flesh

tones, I suspected the changes in color wouldn’t be significant enough

to bother anyone. A professional colorist might take issue with the

finished product, but I don’t think it will bother most members of the

audience, who really just want to get lost in the story and experience

the adventure.

Not all material requires 4K resolution at this point, but it really

helped bring home some of the emotions during the race. For example, we

captured some amazing close-up footage of a devastated competitor who

could not continue the race. What makes a documentary compelling is

extreme emotion, and the JVC 4K camera gave me that moment.

These days, I advise filmmakers to embrace cutting edge technology like

the GY-HMQ10. The old rules may not always apply. Research the story

you want to tell, look at your budget, and decide what technology will

help you shoot your film at a price you can afford.

Bio: Randall P. Dark is president of DARKmania Productions, which is

based in Austin, Texas. Seadrift vs. The Big Guy was first screened in

October 2012 at the Ojai Film Festival in Ojai, Calif.